Information Site About Reproductive System

About Me

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(58)

-

▼

December

(17)

- Syphilis During Pregnancy

- STDs and Pregnancy - Fact Sheet

- URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS in PREGNANCY

- GROUP B STREPTOCOCCUS INFECTION and PREGNANCY

- SWINE FLU and PREGNANCY

- GENITAL HERPES IN PREGNANCY

- LISTERIA and PREGNANCY

- REPIRATORY INFECTIONS DURING PREGNANCY

- HEPATITIS IN PREGNANCY

- CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

- CHLAMYDIA

- RUBELLA

- TOXOPLASMOSIS

- RECTOCELE

- CYSTOCELE

- PROLAPSE OF THE UTERUS

- PELVIC FLOOR

-

▼

December

(17)

Friday, December 4, 2009

What is syphilis?

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) that's caused by a type of bacterium called a spirochete. If left untreated, syphilis can have very serious short- and long-term consequences. Fortunately, with timely antibiotic treatment, these consequences can usually be avoided.

Syphilis is transmitted by direct contact with a sore on an infected person. The most common way to get syphilis is through vaginal, anal, or oral sex, but it's also possible to get it by kissing someone with a syphilitic sore on or around the lips or in the mouth or by exposing an area of broken skin to a sore.

Syphilis can be transmitted to your baby through the placenta during pregnancy or by contact with a sore during birth.

The infection is relatively rare among women in the United States, with 1.1 cases per 100,000 women in 2007, but that number was up 10 percent from 2006. The rates are significantly higher in communities with high levels of poverty, low levels of education, and inadequate access to health care.

The number of babies in the United States born with syphilis also rose – after 14 years of decline – from 339 new cases in 2005 to 382 cases in 2006 to 430 cases in 2007.

What are the symptoms?

In the first stage, known as primary syphilis, the characteristic symptom is a painless and highly infectious sore (or sores) with raised edges called a CHANCRE. The chancre shows up at the site of infection, usually about three weeks after you're exposed to the bacteria, though it may appear earlier or up to three months later.

Because the chancre may be inside your vagina or your mouth, you might never see it. A chancre could also show up on your labia, perineum, anus, or lips, and your lymph nodes may be enlarged in the area where the sore develops.

If you get appropriate treatment at this stage, the infection can be cured. If you're not treated, the sore lasts three to six weeks and then heals by itself. However, the spirochetes are likely to continue to multiply and spread throughout the bloodstream. When this happens, the disease progresses to the next stage, called secondary syphilis.

In the secondary stage, syphilis can have a variety of symptoms that show up in the weeks or months after the sore first appeared, but again, they might not be noticeable.

Without treatment, the symptoms generally clear up on their own within a few months, but the infection stays in your body. The bacteria continue to multiply during this latent phase and can cause very serious problems years later.

In fact, about 1 in 3 people who don't get proper treatment will progress to what's called tertiary syphilis. This late stage of the disease can develop up to 30 years after you were first infected and can cause serious heart abnormalities. Damaging and potentially lethal lesions can develop in your bones, on your skin, and in a host of organs. Fortunately, most people get treated early enough these days that very few end up with tertiary syphilis.

Syphilis can also infect your central nervous system – your brain and spinal cord. This is called neurosyphilis, and it can occur at any stage of the disease. Early on, it may cause problems like meningitis.

Late neurosyphilis can lead to seizures, blindness, hearing loss, dementia, psychosis, spinal cord problems, and eventually death.

How can syphilis affect my pregnancy and my baby's health?

If you don't get treated, there's a very high chance that your baby will be infected, particularly if you're in the early stages of the disease, when it's most infectious. About 40 percent of pregnant women with untreated early syphilis end up having a miscarriage, a stillbirth, or a baby who dies soon after birth. Syphilis also increases the risk of preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction.

Some babies infected with syphilis whose mothers are not treated in a timely fashion during pregnancy develop problems before birth that are visible on an ultrasound. These problems might include an overly large placenta, fluid in their abdomen and severe swelling, and an enlarged liver or spleen.

An infected baby may have other abnormalities at birth, such as a skin rash and lesions around the mouth, genitals, and anus; abnormal nasal secretions; swollen lymph glands; pneumonia; and anemia.

Most babies don't have these symptoms initially, but without treatment they develop some symptoms within the first month or two after birth. And whether or not there are obvious symptoms early on, if the disease isn't treated, babies born with syphilis may end up with more problems years later, such as bone and teeth deformities, vision and hearing loss, and other serious neurological problems.

That's why it's critical for women to be tested and treated during pregnancy, and for any baby who may have syphilis at birth to be fully evaluated and treated as well.

Will I be tested for syphilis during my pregnancy?

Yes. Even though the infection is relatively rare, it's considered vitally important to detect and treat syphilis during pregnancy. The CDC recommends that all pregnant women be screened for the infection at their first prenatal visit, and some states require that all women be tested again at delivery.

If you live in a community where syphilis is prevalent or you're otherwise at high risk, you should be tested again at 28 weeks and at delivery. You'll also be retested for syphilis if you've contracted another STI during your pregnancy or if you or your partner develops symptoms of syphilis.

Because it takes about four to six weeks after exposure to get a positive result from the blood test, the result may be negative if you're tested too soon.

So if you had high-risk sex a few weeks before your test or your partner recently had symptoms, tell your practitioner so you can be tested again in a month. If your screening test is positive, the lab will perform a more specific test on your blood sample to tell for sure whether you have syphilis.

Having syphilis makes you more susceptible to HIV if you're exposed to it, so if you test positive for syphilis, you should also be tested (or retested) for HIV and other STIs.

And if you have primary syphilis, you'll need to be tested for HIV again in three months

How is syphilis treated during pregnancy?

Penicillin is the only antibiotic that's both safe to take during pregnancy and able to successfully treat both mother and baby for syphilis. If you have syphilis, you'll get treated with one or more injections of penicillin, depending on the stage of the disease and whether you have neurosyphilis. (If you have any symptoms of neurosyphilis, you'll have a spinal tap to check for it.) If you're allergic to penicillin, you'll need to be desensitized to the drug first, so you can receive it.

In many pregnant women, treatment for syphilis causes a temporary reaction that may include fever, chills, headache, and muscle and joint aches. These symptoms tend to appear several hours after treatment and go away on their own in 24 to 36 hours.

The treatment may also cause some changes in your baby's heart rate, and if you're in the second half of your pregnancy, it may cause contractions. (If you notice any contractions or a decrease in fetal movement, you should call your caregiver immediately. In some cases, your caregiver may opt to treat you in the hospital so you can be monitored.)

Your partner will also need to be tested, and he'll be treated if he's positive or has had sexual contact with you in the last three months, even if his blood test is negative. You need to refrain from sexual contact until both of you have been treated. After treatment, you'll have regular blood tests to make sure the infection has cleared and you haven't been reinfected, and you'll have an ultrasound to check on your baby.

How can I avoid getting syphilis?

Have sex only with a partner who has sex only with you and has tested negative for syphilis. While condoms can prevent transmission of HIV and other STIs, they only offer protection from syphilis if the sore is on your partner's penis – they won't protect you from sores that aren't covered by the condom.

Remember, too, that you can get syphilis if a partner's sore touches any of your mucous membranes (such as in your mouth or vagina) or broken skin (a cut or scrape).

If you've had syphilis once, that doesn't mean you can't get it again. You can become reinfected.

If there's a possibility that you've been exposed to syphilis or any other STI during pregnancy, or you or your partner has any symptoms, tell your practitioner right away so you can be tested and treated if necessary.

Can Pregnant Women Become Infected With STDs

Yes, women who are pregnant can become infected with the same sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) as women who are not pregnant. Pregnancy does not provide women or their babies any protection against STDs. The consequences of an STD can be significantly more serious, even life threatening, for a woman and her baby if the woman becomes infected with an STD while pregnant. It is important that women be aware of the harmful effects of STDs and knows how to protect themselves and their children against infection.

How Common Are STDs In Pregnant Women

Some STDs, such as genital herpes and bacterial vaginosis, are quite common in pregnant women in the United States. Other STDs, notably HIV and syphilis, are much less common in pregnant women. The table below shows the estimated number of pregnant women in the United States who are infected with specific STDs each year.

| STDs | Estimated Number Of Pregnant Women |

| Bacterial Vaginosis | 1.080.000 |

| Herpes Simplex Virus 2 | 880-.000 |

| Chlamydia | 100.000 |

| Trichomoniasis | 124.000 |

| Gonorrhoea | 13,200 |

| Hepatitis B | 16.000 |

| HIV | 6.400 |

| Syphilis | < 1.000 |

How Do STDs Affect A Pregnant Women and Her Baby

STDs can have many of the same consequences for pregnant women as women who are not pregnant. STDs can cause cervical and other cancers, chronic hepatitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and other complications. Many STDs in women are silent; that is, without signs or symptoms.

STDs can be passed from a pregnant woman to the baby before, during, or after the baby’s birth. Some STDs (like syphilis) cross the placenta and infect the baby while it is in the uterus (womb). Other STDs (like gonorrhea, chlamydia, hepatitis B, and genital herpes) can be transmitted from the mother to the baby during delivery as the baby passes through the birth canal. HIV can cross the placenta during pregnancy, infect the baby during the birth process, and unlike most other STDs, can infect the baby through breastfeeding.

A pregnant woman with an STD may also have early onset of labor, premature rupture of the membranes surrounding the baby in the uterus, and uterine infection after delivery.

The harmful effects of STDs in babies may include stillbirth (a baby that is born dead), low birth weight (less than five pounds), conjunctivitis (eye infection), pneumonia, neonatal sepsis (infection in the baby’s blood stream), neurologic damage, blindness, deafness, acute hepatitis, meningitis, chronic liver disease, and cirrhosis. Most of these problems can be prevented if the mother receives routine prenatal care, which includes screening tests for STDs starting early in pregnancy and repeated close to delivery, if necessary. Other problems can be treated if the infection is found at birth.

Should Pregnant Women Be Tested For STDs ?

Yes, STDs affect women of every socioeconomic and educational level, age, race, ethnicity, and religion. The CDC 2006 Guidelines for Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Diseases recommend that pregnant women be screened on their first prenatal visit for STDs which may include:

In addition, some experts recommend that women who have had a premature delivery in the past be screened and treated for bacterial vaginosis at the first prenatal visit.

Pregnant women should ask their doctors about getting tested for these STDs, since some doctors do not routinely perform these tests. New and increasingly accurate tests continue to become available. Even if a woman has been tested in the past, she should be tested again when she becomes pregnant.

Can STDs Be Treated During Pregnancy ?

Chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, trichomoniasis, and bacterial vaginosis (BV) can be treated and cured with antibiotics during pregnancy. There is no cure for viral STDs, such as genital herpes and HIV, but antiviral medication may be appropriate for pregnant women with herpes and definitely is for those with HIV. For women who have active genital herpes lesions at the time of delivery, a cesarean delivery (C-section) may be performed to protect the newborn against infection. C-section is also an option for some HIV-infected women. Women who test negative for hepatitis B, may receive the hepatitis B vaccine during pregnancy.

How Can Pregnant Women Protect Themselves Against Infection ?

The surest way to avoid transmission of sexually transmitted diseases is to abstain from sexual contact, or to be in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested and is known to be uninfected.

Latex condoms, when used consistently and correctly, are highly effective in preventing transmission of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Latex condoms, when used consistently and correctly, can reduce the risk of transmission of gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis Correct and consistent use of latex condoms can reduce the risk of genital herpes, syphilis, and chancroid only when the infected area or site of potential exposure is protected by the condom. Correct and consistent use of latex condoms may reduce the risk for genital human papillomavirus (HPV) and associated diseases (e.g. warts and cervical cancer).

What is a UTI?

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is caused when the urinary system becomes infected by bacteria.

UTIs are common in women aged between 20 and 50.

About 50 per cent of women will have at least one UTI during their lifetime.

If left untreated, UTIs can be quite painful - and even dangerous because the infection can travel upwards and reach the kidneys. If a kidney infection is left untreated during pregnancy it could make you very poorly and could lead to your baby being born with a low birth weight or being born prematurely.

The changes your body goes through during pregnancy make you more susceptible to UTIs. Progesterone relaxes the muscles of your ureters, the tubes that connect your kidneys to your bladder. This slows down the flow of urine from your kidneys to your bladder. Your enlarging uterus (womb) has the same effect. This is an ideal opportunity for bacteria because they have more time to grow before they're flushed out.

Symptoms of a UTI can include:

- Pain or a burning sensation when passing urine

- Pain in your pelvis, the lower part of your abdomen, the lower part of your back, or in your side (usually only one side)

- A feeling that you are unable to urinate fully

- Shaking

- Raised temperature

- Feeling hot and cold by turns

- Nausea and vomiting

- Frequent need to go to the toilet

- Uncontrollable urge to pass urine (incontinence)

- Cloudy, bloody, or bad-smelling urine

- Change in the amount of urine passed (either more or less)

- Pain during sexual intercourse

I've always been susceptible to urinary tract infections. What will happen if I get one while I'm pregnant?

UTIs can be safely treated with antibiotics during pregnancy. You will probably be prescribed a three to seven-day course. Talk to your GP or midwife as soon as you notice any symptoms because an untreated UTI can lead to a kidney infection, which may in turn cause premature labour.

What can I do to avoid getting an infection?

Taking the following precautions should reduce the risk of getting a UTI:

- After going to the toilet, wipe yourself from front to back to prevent bacteria from the back passage being spread to the front passage.

- Wash thoroughly between your legs every day, but avoid strong soaps, douches, antiseptic creams, and feminine hygiene products (urethra) that can kill the "good" bacteria and irritate your sensitive urinary tract.

- Empty your bladder completely when you go to the toilet.

- Go to the toilet soon after having sexual intercourse.

- Avoid long or very frequent baths.

- Wear cotton knickers and avoid tights.

- Change underwear and tights every day.

- Treat constipation promptly, as this may increase your risk of getting a UTI.

- Have plenty of liquids, especially water, to drink.

- Drink cranberry juice, if you suffer from UTIs repeatedly. Cranberry juice can reduce levels of bacteria in the urinary tract and prevent new bacteria from taking hold, so helping to prevent minor infections (sprays or powders). Don't drink cranberry juice if you are taking warfarin.

What is Group B streptococcus?

Group B streptococcus, or GBS, also known as group B strep, is one of many different bacteria that normally live in our bodies. Approximately one third of us "carry" GBS in our intestines without knowing.

About a quarter of women also have it in their vagina (RCOG 2003:1). Most don't know it's there, as it doesn't usually cause problems or symptoms.

However, in rare cases GBS can cause serious illness and even death in newborn babies.

Although these cases are unusual, GBS is the most common cause of severe infection in newborns, particularly in the first week after birth (known as an early onset infection) (RCOG 2003:1). In the UK, about 340 babies a year develop a GBS infection.

How do I know if I carry GBS?

If you do carry GBS, you won't necessarily know as there aren't usually any ill effects. There is a test available for GBS, but this isn't done routinely in pregnancy (see Why isn't there a national screening programme for GBS? below).

Pregnant women often find out that they have GBS by chance, when they have a vaginal swab taken to check for something else. Also, GBS can come and go, so even if you've had a positive test earlier in pregnancy, you may not have GBS as you approach delivery.

It's important for pregnant women and their carers to know when babies are most likely to develop a GBS infection and what the signs of GBS infection in babies are.

Now I'm pregnant, what should I know about GBS?

Most babies exposed to GBS before or during birth suffer no ill effects. However, around one in 2000 babies in the UK develops a GBS infection (Heath et al cited by RCOG 2003:1; RCOG 2003:3). Sadly, about one in 10 of these babies die.

It isn't clear why some babies develop an infection while others don't. What is clear is that most GBS infection in newborn babies can be prevented.

Women in higher-risk situations can be given intravenous antibiotics either from the start of labour or from when their waters break (whichever comes first) until their baby is born.

Caesareans are not recommended to prevent GBS infection in babies as they don't eliminate the risk of GBS to the baby (GBSS 2007a).

Very occasionally GBS causes infection of the uterus or urinary tract in new mothers.

Is my baby at risk of developing GBS infection?

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has identified a number of factors that help to predict whether your baby is more likely to develop a GBS infection (RCOG 2003:3-6).

These include, if:

- You go into labour prematurely (before 37 weeks of pregnancy)

- Your waters break 18 hours or more before you have your baby

- You have a raised temperature (38 degrees C / 100 degrees F or higher) during labour

- You have previously had a baby infected with GBS

- You have been found to carry GBS in your vagina and/or rectum during your current pregnancy

- GBS has been found in your urine during this pregnancy (this should be treated when diagnosed, but even if you have been treated, extra precautions should still be considered during labour - see How should my labour and delivery be managed?, below).

How should my labour and delivery be managed?

If you don't fall into one of the higher-risk groups, above, your baby is very unlikely to develop a GBS infection.

If you are higher-risk, research shows that having intravenous antibiotics from the start of your labour or from when your waters break until your baby is born can prevent most GBS infections in newborn babies.

Ideally, you should have intravenous antibiotics for at least two hours before your baby is born and every four hours during labour (RCOG 2003:6). There are some risks with taking antibiotics for you and your baby so your doctor will discuss your particular case with you to see whether treatment is the best option for you.

If you have two or more of the above risk factors then your doctor is much more likely to recommend treatment during labour to reduce the risk of your baby developing an infection (RCOG 2003:6).

If you are having a planned caesarean there is no need for intravenous antibiotics unless your waters have broken or labour has already started (RCOG 2007:6).

If your baby is at higher risk of developing a GBS infection, once he is born:

- He should be examined by a paediatrician immediately

- If both you and he are completely healthy, and you had full treatment with intravenous antibiotics during labour, he may be given intravenous antibiotics

- If both you and he are healthy, but you have not received full treatment with intravenous antibiotics during labour, he may be started on intravenous antibiotics until he's given the all clear

- If you or he shows signs of GBS infection, he should be started on intravenous antibiotics immediately

The best way to treat newborns at risk of GBS infection is an area that doctors are still researching, which is why in some cases your baby may or may not be given antibiotics.

What are the risks of treatment?

Most women and babies can safely be given penicillin as the antibiotic treatment for GBS without any ill-effects. However, a small number of people are allergic to penicillin and could have a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis), which can be fatal.

Women who are known to be allergic to penicillin can be given another antibiotic instead (RCOG 2003:6).

Other less severe side-effects of antibiotic treatment include diarrhoea and nausea. However, there are concerns that antibiotics may affect the balance of a baby's bacterial flora in the gut (RCOG 2003:1).

These adverse effects make some doctors more cautious about using antibiotics if there is not a clear need to do so, particularly for newborns. Some prefer a "watch and wait" approach for the first 12 hours after birth before starting a course of antibiotics that may not be needed (RCOG 2003:7-10).

What are the signs of GBS infection in a baby?

GBS infections in babies are usually "early-onset" (within seven days of birth), with 90 per cent occurring within 12 hours of birth (RCOG 2003:7-8).

In many cases, symptoms of GBS infection in babies can be recognised at or soon after birth (RCOG 2003:7).

Typical signs of early-onset GBS infection include:

- Grunting

- Poor feeding

- Lethargy

- Irritability

- Low blood pressure

- Abnormally high or low temperature, heart rate and/or breathing rate

(GBSS 2007b)

Although more unusual, GBS infections can also develop when the baby is seven or more days old ("late-onset" GBS), usually as meningitis with septicaemia.

Some warning signs of late-onset GBS infection may include:

- Fever

- Poor feeding and/or vomiting

- Drowsiness

(GBSS 2007b)

Signs of meningitis in babies may include, as well as any of the signs listed above:

- Shrill or moaning cry or whimpering

- Dislike of being handled, fretful or irritable

- Tense or bulging fontanelle (soft spot on head)

- Floppy and listless or stiff with jerky movements

- Blank, staring or trance-like expression

- Being difficult to wake

- Low or high breathing rate

- Turns away from bright lights

- Skin that is pale, blotchy or turning blue

(GBSS 2007b; DH 2006)

Red or purple spots that do not fade under pressure (such as when pressed firmly with the side of a glass) are a sign of septicaemia (DH 2006).

Early diagnosis and treatment are vital in late-onset GBS infection or meningitis. If your baby shows any of the signs above, call your GP immediately.

If your GP isn't available, go straight to your nearest accident and emergency department. The risk of your baby developing GBS decreases with age; GBS infections in babies are rare after one month of age and virtually unknown after three months (GBSS 2007).

Most babies survive with treatment, but meningitis can leave some babies with long term problems - visit The Meningitis Trust for more information.

Why isn't there a national screening programme for GBS?

There are strict criteria that have to be met before a national screening programme for any disease can be introduced (UK NSC 2003). These include weighing up factors such as the accuracy of a screening test and the risks versus benefits of treatment.

In the case of GBS, experts are not convinced that a lab test screening programme would do more good than harm. Reasons for this include:

- Current lab testing through the NHS in the UK is not reliable enough to recommend that all pregnant women be swabbed and tested during late pregnancy

- There are concerns that the widespread use of antibiotics during labour could increase the risks of severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) and make the labour and newborn period too medicalised

- The rates of bacteria resistant to antibiotics could increase

- Newborns affected by antibiotics during labour may possibly be more likely to develop allergies and have poor immune systems (RCOG 2003:1-4)

I'm carrying GBS - what now?

If you have been affected by GBS in a previous pregnancy, or you are found to be carrying it in your current pregnancy, talk to your midwife or obstetrician and agree a pregnancy and birth plan that will protect your baby from the infection.

In the vast majority of cases your pregnancy can be managed so your baby is protected and born healthy and free from GBS.

Your baby is not at risk of catching GBS from breastfeeding (RCOG 2003:8) so there is no need to change your plans if you intend to breastfeed your baby.

What is swine flu (H1N1)?

Swine flu (H1N1) is a highly contagious type of flu, with symptoms similar to seasonal flu. Swine flu has spread so quickly because it is a new virus, so most of us have not built up any immunity to it. The H1N1 virus is called swine flu because it is thought to originate from pigs.

Swine flu was first reported in Mexico in April 2009. Two months later, the World Health Organisation (WHO) raised a worldwide pandemic alert. This means that the disease has spread to many countries around the world.

How does swine flu spread?

Swine flu spreads in the same way as other flu viruses, through droplets from the coughs and sneezes of people who are infected. It spreads easily, particularly in enclosed spaces where there is close contact between people (WHO 2009).

What are the symptoms of swine flu?

Swine flu affects people differently. Most people who catch the virus have only mild symptoms (BMJ 2009a), but some people develop complications such as dehydration, pneumonia (an infection in the lungs) or difficulty breathing (NHS Choices 2009a).

There is evidence that pregnant women are four times more likely to develop complications from swine flu than non-pregnant women (DH 2009a). However, for most pregnant women the symptoms of swine flu are similar to ordinary flu. These are:

- sudden fever

- tiredness

- sore throat

- runny nose

- cough

- headache

- muscle and joint pain

- Acute abdominal pain

- Diarrhoea

- Vomiting (NHS Choices 2009b)

I'm pregnant. Am I more at risk of catching swine flu?

Pregnant women are not known to be more at risk of catching swine flu. However, if you do catch the flu you have a greater risk of developing complications (RCOG/DH 2009). This is because your immunity to infection is slightly lowered to stop your body rejecting your unborn baby. This also makes it particularly important that you are careful to protect yourself (see below) (CDC 2009b).

Can I be vaccinated against swine flu?

A vaccine for swine flu is available.

Pregnant women will be a priority in the early stages of the vaccination programme (NHS Choices 2009a).

The vaccine is given to pregnant women in two doses, with a three-week interval. It is recommended that all pregnant women have the swine flu vaccine (BMJ 2009b).

Are there other ways I can protect myself against swine flu?

You can reduce your risk of infection by avoiding unnecessary travel and keeping away from crowds. Wherever possible, try to avoid contact with people who have flu-like symptoms or you know have swine flu (Directgov 2009c).

Unless you have swine flu symptoms, you can carry on attending your antenatal appointments. You should also follow the hygiene rules recommended for everyone:

- Cover your nose and mouth with a disposable tissue when you cough and sneeze and throw it away after using it (Directgov 2009b).

- If you don't have a tissue to hand, cover your mouth with the inner part of your elbow when you cough or sneeze. This will avoid passing the infection to your hand and will minimise spreading the disease (WHO 2009).

- After coughing and sneezing, wash your hands with warm water and soap. Rub both sides of your soapy hands for at least for 15 seconds and rinse with lots of water. If soap and water are not available, use alcohol-based disposable hand wipes or gel sanitisers (CDC 2009a).

- Don't touch your eyes, nose or mouth, because the germs spread very quickly (WHO 2009).

- Wash your hands frequently. The virus can live for up to 24 hours on surfaces such as doorknobs and telephones (NHS Choices 2009a).

- Eat a healthy diet, including plenty of fresh fruit, vegetables and wholegrain foods that will give you the minerals and antioxidant vitamins that help to fight infections (BDA 2009).

Could swine flu affect my developing baby?

We know that with ordinary seasonal flu, your baby is well protected against the virus within your uterus (womb). Swine flu is a new strain of flu, so we don't yet know everything about it, but the risk of infection for your developing baby is not thought to be high (RCM 2009).

Fever in early pregnancy is known to slightly increase the risk of neural tube defects, such as spina bifida, so it's important to control a high temperature. A very small number of pregnant women with swine flu develop complications, such as pneumonia, that can lead to miscarriage or their baby being born early. These risks are greater during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

The vast majority of pregnant women with swine flu make a full recovery and go on to have a healthy baby at full-term (HPA 2009).

How long do people stay contagious?

People who have the swine flu virus can be contagious for up to seven days after the onset of the illness. Children, especially younger ones, may be contagious for longer (CDC 2009a).

What should I do if I or somebody in my family has symptoms of swine flu?

If you're pregnant, call your doctor immediately to explain what's happening and tell her you are pregnant (CDC 2009b). Swine flu can be more severe in people with compromised immune systems, so she will also need to know if you, or anyone else in your family, have any other health problems (NHS Choices 2009b). Your doctor may prefer to give you a diagnosis over the phone, because the virus is highly contagious (NHS Choices 2009a).

If you think someone in your family has swine flu, log onto the National Pandemic Flu Service, which can dispense antiviral drugs. If you are pregnant or your child is under one, this service will not be suitable for you and you will still need to speak to your doctor (Directgov 2009).

You can also call NHS Direct on 0845 4647 for advice.

How can swine flu be treated?

Fever is one of the symptoms of swine flu, so if you have a high temperature it's important to control it. Try your best to cool yourself down with a fan or tepid sponge. You can safely take paracetamol-based cold remedies (RCOG 2009). However, if you are pregnant, you should not take aspirin or anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen (NHS Choices 2009c).

There is no cure for swine flu, but antiviral drugs will relieve the symptoms and help you to recover faster. They will also reduce the likelihood of you developing complications. It's recommended that pregnant women are offered antiviral treatment if it's suspected they have swine flu, even before it's been confirmed (RCOG/DH 2009).

Most pregnant women will be prescribed the antiviral drug Relenza. This antiviral is inhaled, so reaches the throat and lungs and does not build up in your blood stream (NHS Choices 2009d). If you have a health condition that makes it difficult for you to inhale a preparation, such as asthma, you will be offered Tamiflu (DH 2009b).

The risk of taking antiviral treatments in pregnancy is extremely small, and much smaller than the risks posed by the symptoms of swine flu (NHS Choices 2009a).

What is genital herpes?

Genital herpes is caused by the herpes simplex virus which also causes cold sores around and in the mouth. Genital herpes is usually caused by herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), while cold sores are usually caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). However, genital herpes can also be caused by HSV-1. Once you have been infected with a herpes virus it stays in your body for life, only becoming active every now and again.

How might genital herpes affect my pregnancy?

If you had genital herpes before you became pregnant then the risk of your baby becoming infected is very low, even if you have an outbreak during your pregnancy or during labour. This is because your body has had time to develop antibodies to the herpes simplex virus and this immunity is passed on to your baby during pregnancy. Your baby will continue to be immune for up to three months after the birth.

If you catch genital herpes for the first time in the first or second trimester of your pregnancy, there is a slight risk that it will affect your developing baby. The infection has been linked to :

- Miscarriage,

- Intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR),

- Premature labour,

- Microcephaly (where the baby's brain is underdeveloped) and

- Hydrocephaly (where fluid builds up around the baby's brain) but this happens very rarely.

Your doctor will probably refer you to a genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinic where you will be given a 5-day course of an oral antiviral medicine, usually acyclovir.

The ACYCLOVIR wll help you to reduce your discomfort and speed up the healing or your sores. It is safe to use in pregnancy.

Your baby is at greater risk if you catch genital herpes for the first time in late pregnancy before you have had time to develop antibodies to the virus and to pass this immunity on to your baby. Your baby can catch the virus through direct contact with an active sore, which is weeping or inflamed, during birth. If a baby catches the infection at birth it is called neonatal herpes. About four in ten babies develop neonatal herpes when born vaginally to women with a first infection when they come to give birth.

In the UK, only one or two babies in 100,000 catch neonatal herpes, but it can be very serious and even fatal. Neonatal herpes can cause infection in a baby's skin, eyes or mouth and may damage the brain or other organs. If your baby does catch neonatal herpes, effective treatment with antiviral medicine for you and your baby can help prevent and minimise long term damage to your baby's health.

Will I need to have a caesarean?

If you suspect you have an active genital herpes infection in the last trimester of pregnancy it is vital that you tell your midwife or doctor. If you have never had herpes before then you will probably be advised to have a planned caesarean section, particularly if you have your first outbreak in the last six weeks of pregnancy. This is to minimise the risk of transmitting the virus to your baby.

If you want to go ahead with a vaginal delivery, then your obstetrician will try to avoid any invasive procedures such as ventouse or forceps and will give you intravenous acyclovir during labour and delivery as this may reduce the risk of your baby catching herpes. Your newborn baby will also be given acyclovir.

If it is not your first infection, you will probably be given acyclovir daily for the last four weeks of pregnancy. You will not be advised to have a caesarean as your baby will probably have immunity to the virus.

Can I breastfeed if I have herpes?

The herpes virus is not transmitted through breastmilk so having herpes shouldn't stop you from breastfeeding, providing you don't have any sores on your breasts. Make sure that sores elsewhere on your body are covered and wash your hands frequently and carefully. If you are taking acyclovir, it will be excreted in your breastmilk but is not thought to be harmful.

What are the symptoms of a genital herpes infection?

Symptoms vary a lot from person to person. What most people do find is that symptoms are usually worse, and last longer, the first time they have a herpes outbreak. Symptoms of a primary or first infection may include:

painful sores over your genitals and buttocks

- itching

- stinging when passing urine

- vaginal discharge

- swollen glands in the groin area

- flu-like symptoms including fever, headache and muscle aches

A primary episode can last two to three weeks.

With a second or later infection you may get no symptoms at all or just a small area of irritation. If it is not your first outbreak, it will probably be over within three to five days.

Whether or not you have symptoms, it is important to remember that you are still contagious during a herpes recurrence. In fact, most infections occur when the person passing it on has no noticeable symptoms. This is why it is important to tell your midwife if you or your partner suspect you may have had a herpes outbreak in the past.

How can I avoid catching the virus while I am pregnant?

If your partner has genital herpes you need to be particularly careful when you are pregnant. As the virus can be transmitted without your partner knowing that he is having an outbreak there are no foolproof methods to avoid catching herpes. In fact, the virus is most infectious when, or just before, symptoms appear. You can catch herpes from penetrative and non-penetrative sex (vaginal or anal), from oral sex, and by sharing sex toys. Condoms may help to reduce the risk of catching herpes from your partner, or you may want to avoid sex altogether. You should also be aware that you can catch genital herpes from your partner if he has oral herpes and performs oral sex.

During pregnancy, it is important to be aware of what you put inside your body. You should be aware of what is good to eat and also what is not so good to eat. Listeria is a type of bacteria that can be found in some contaminated foods. Listeria can cause problems for both you and your baby. Although listeriosis (the illness from ingesting Listeria) is rare, pregnant women are more susceptible to it than non-pregnant healthy adults.

What is Listeria?

Listeria monocytogenes is a type of bacteria that is found in water and soil. Vegetables can become contaminated from the soil, and animals can also be carriers. Listeria has been found in uncooked meats, uncooked vegetables, unpasteurized milk, foods made from unpasteurized milk, and processed foods.

Listeria is killed by pasteurization and cooking. There is a chance that contamination may occur in ready-to-eat foods such as hot dogs and deli meats because contamination may occur after cooking and before packaging.1

What are the risks of a pregnant woman getting listeriosis?

According to the Center of Disease Control (CDC), an estimated 2,500 persons become seriously ill each year in the United States and among these, 500 will die. According to research, pregnant women account for 27% of these cases. CDC claims that pregnant women are 20 times more likely to become infected than non-pregnant healthy adults.

How will I know if I have listeriosis?

Symptoms of listeriosis may show up 2-30 days after exposure. Symptoms in pregnant women include mild flu-like symptoms, headaches, muscle aches, fever, nausea, and vomiting. If the infection spreads to the nervous system it can cause stiff neck, disorientation, or convulsions. Infection can occur at any time during pregnancy, but it is most common during the third trimester when your immune system is somewhat suppressed. Be sure to contact your health care provider if you experience any of these symptoms.

Can listeriosis harm my baby?

If you are pregnant and are infected with listeriosis, you could experience:

- Miscarriage

- Premature delivery

- Infection to the newborn

- Death to the newborn (about 22% of cases of perinatal listeriosis result in stillbirth or neonatal death)

Early treatment may prevent fetal infection and fetal death.

How is listeriosis treated?

Listeriosis is treated with antibiotics during pregnancy. These antibiotics, in most cases, will prevent infection to the fetus and newborn. These same antibiotics are also given to newborns with listeriosis.

What can I do to protect my baby from listeriosis?

Following these guidelines can greatly reduce your chances of contracting Listeriosis.

Eat hard cheeses instead of soft cheeses: The CDC has recommended that pregnant women avoid soft cheeses such as feta, Brie, Camembert, blue-veined cheesesl and Mexican style cheeses such as queso fresco, queso blanco and panela.

Hard cheeses such as cheddar and semi-soft cheeses such as mozzarella are safe to consume. Pasteurized processed cheese slices and spreads such as cream cheese and cottage cheese can also be safely consumed. The most important thing to do is read the labels!

Be cautious when eating hot dogs, luncheon meats, or deli meats unless they are properly reheated to steaming( or 160 degrees F.): Eating out at certain restaurants that provide deli meat sandwiches is not recommended for pregnant women since they do not reheat their deli meats. Restaurants such as Subway recommends that pregnant women eat the following non-luncheon meat items such as meatball, steak and cheese, roasted chicken, and tuna (limit 2 servings a week).

Do not eat refrigerated pates or meat spreads.

Do not eat refrigerated smoked seafood unless it is contained in a cooked dish, such as a casserole.

Practice safe food handling:

- Wash all fruits and vegetables

- Keep everything clean including your hands and preparation surfaces

- Keep your refrigerator thermometer at 40 degrees or below

- Clean your refrigerator often

- Avoid cross contamination between raw and uncooked foods (this includes hot dog juices)

- Cook foods at proper temperatures (use food thermometers) and reheat all foods until they are steaming hot (or 160 F)

Proper Temperatures for Cooking Foods:

- Chicken: 165-180 F

- Egg Dishes: 160 F

- Ground Meat: 160-165 F

- Beef, Medium well: 160 F

- Beef, Well Done: 170 F (not recommended to eat any meat cooked rare)

- Pork: 160-170 F

- Ham (raw): 160 F

- Ham (precooked): 140 F

Refrigerate or freeze food promptly.

What is a viral respiratory infection?

A viral respiratory infection is a contagious illness that can affect your respiratory tract (breathing) and cause other symptoms.

The flu and the common cold are examples of viral respiratory infections.

Other examples of respiratory viruses are:

- Chickenpox (varicella)

- Fifth disease

- Cytomegalovirus (say: "si-to-meg-ah-low-vi-russ")

- Rubella (also called German measles)

What if I'm exposed to a viral respiratory infection when I'm pregnant?

Pregnant women can be exposed to people with viral infections at work and at home. Most of the time, the woman doesn't get infected. Even if she does, most viruses won't hurt her baby. However, some viruses can cause miscarriage or birth defects in the baby.

If you're exposed to chickenpox, fifth disease, cytomegalovirus or rubella while you're pregnant, you should tell your doctor right away. Your doctor will want to know how much contact you've had with the infected person.

Here are some questions your doctor may ask you:

- Did you touch or kiss the infected person

- How long were you in contact with the the infected person?

- When did the infected person get sick?

- Did a doctor diagnose the infected person's illness? Were any tests done?

What should I do if I'm exposed to CHICKENPOX?

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella virus and is highly contagious. It can be serious during pregnancy. Sometimes, chickenpox can cause birth defects. If you've had chickenpox in the past, then it is unlikely you will catch it again and your baby will be fine. If you have not had chickenpox or if you're not sure, you should see your doctor right away. Your doctor will test your blood to see if you are immune.

Many people who don't remember having chickenpox are immune anyway. If your blood test shows that you're not immune, you can take medicines to make your illness less severe and possibly help protect your baby from chickenpox.

What should I do if I'm exposed to FIFTH disease?

Fifth disease is a common virus in children. Half of all adults are susceptible to fifth disease and can catch it from children.

Children who have fifth disease usually develop a rash on their body and have cold-like symptoms. They may have red cheeks that look like they've been slapped or pinched. Adults who get fifth disease don't usually have the "slapped cheek" rash. Adults who contract fifth disease usually have very sore joints.

If you get fifth disease early in your pregnancy, you could have a miscarriage. Fifth disease can also cause birth defects in your baby (such as severe anemia). If you're exposed to fifth disease, call your doctor. Your doctor may have you take a blood test to see if you're immune. You may also need an ultrasound exam to see if the baby has been infected.

What if I'm exposed to CYTOMEGALOVIRUS?

Cytomegalovirus usually doesn't cause any symptoms, so you probably won't know if you have it. It's the most common infection that can be passed from mother to baby.

Cytomegalovirus affects 1 of every 100 pregnant women. It can cause birth defects (such as hearing loss, development disabilities or even death of the fetus).

It's important to prevent cytomegalovirus because there's no way to treat it. Women who work in day care centers and in a health care setting have the highest risk of getting infected. Pregnant women with these jobs should wash their hands after handling diapers and avoid nuzzling or kissing the babies. If you think you've been exposed to a person who has cytomegalovirus, you should see your doctor right away.

What if I'm exposed to RUBELLA (German measles)?

Since 1969, almost all children have had the rubella vaccine, so it is a rare disease today.

At the first prenatal visit, all pregnant women should be tested to see if they're immune to rubella. Women who are not immune to rubella should get the vaccine after the baby is born. It's even better to be tested before you get pregnant, so that you can get the vaccine if you need it.

If you're exposed to rubella when you're pregnant and are not immune, severe birth defects or death of the fetus can occur. Symptoms of rubella in adults is typically joint pain and occasionally an ear infection. Talk to your doctor if you are experiencing these symptoms.

What if I'm exposed to INFLUENZA?

Influenza hardly ever causes birth defects. It can be more serious for the mother if she gets the flu while pregnant. You might get very sick. If you'll be pregnant during the flu season (from October through March), you should get a flu shot in the fall.

What about other viral infections?

Most other respiratory viruses (such as regular measles, mumps, roseola, mononucleosis ["mono"] and bronchiolitis) don't seem to increase the normal risk for birth defects. In normal pregnancies, the risk of serious birth defects is only 2% to 3%. To protect yourself from all infectious viruses, wash your hands frequently (especially after using the restroom or before a meal).

Effects of Hepatitis B Virus Infection

Hepatitis B virus is one of a number of viruses that attack and damage the liver. (Other types include hepatitis A, hepatitis C, and hepatitis D.) The liver is an organ located in your upper abdomen.

Hepatitis B virus is passed from person to person by way of infected body fluids. These body fluids include:

-

Blood

-

Semen

-

Vaginal fluids

-

Saliva

Infection with hepatitis B virus can cause major health problems. A person infected with this virus may not show any signs of being infected, but can pass it on to others.

Infection with hepatitis B virus is a special problem for pregnant women. Not only does a pregnant woman face the risks of hepatitis herself, she also can pass the virus to her baby. About 1 in every 500–1,000 pregnant women has hepatitis when she gives birth. More pregnant women may be infected but not show any signs.

The virus can be spread through sexual contact.

The virus also can be passed to someone who comes in contact with the blood of an infected person. This can occur in many different ways, for instance by sharing needles with someone who is infected with the virus. It also can be passed during childbirth.

Infected persons are at risk for many health problems. The virus infects the liver and can cause chronic (long-term) hepatitis.

Chronic hepatitis can be life threatening. Persons with chronic hepatitis have a greater chance of getting certain types of liver disease, such as cirrhosis (hardening) of the liver and cancer of the liver.

The symptoms of hepatitis can include:

-

Fatigue

-

Loss of appetite

-

Nausea

-

Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes)

-

Dark urine

-

Soreness in the liver

-

Muscle aches

Some people infected with the virus do not become immune to it, but show no sign of infection. Such people are called carriers. They still can pass the virus to someone else even though they do not have any symptoms. A woman who is a carrier can pass the virus to her baby at birth. Carriers sometimes become sick later in life.

Effects During Pregnancy

When a pregnant woman is infected with hepatitis B virus, there is a chance she will infect her fetus. Whether the baby will get the virus depends on when infection occurred. If it was early in pregnancy, the chances are less than 10% that the baby will get the virus. If it was late in pregnancy, there is up to a 90% chance that the baby will be infected.

Hepatitis can be severe in babies. It can threaten their lives. Even babies who appear well may be at risk for serious health problems.

Infected newborns have a high risk (up to 90%) of becoming carriers. They, too, can pass the virus to others. When they become adults, these carriers have a 25% risk of dying of cirrhosis of the liver or liver cancer.

Testing for the Virus

A blood test can show whether someone has been infected with hepatitis B virus. For the test, a small sample of blood is taken and tested for a special protein—called an antigen—that is found in blood infected with the virus.

If your test result is negative, it means you were not infected with the virus at the time the test was done. If your test result is positive, it means you have been infected with the virus and can infect others. This includes your baby if you are pregnant. Your doctor will want to do more tests to learn whether your liver is still healthy. A positive test result means that your children, your sexual partner(s), and others living in your household are at risk of infection. They should be told about testing and vaccination. They will need to decide whether to have them done.

All pregnant women should be tested for the virus. The test should be done early enough in pregnancy to allow time to prepare treatment for the baby and to test family members if your test result is positive.

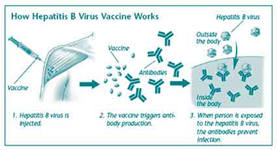

Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus

There are steps you can take to try to prevent being infected with hepatitis B virus. One thing you can do is practice safe sex. The use of condoms during sex helps to prevent infection with hepatitis B virus and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Do not share needles used to inject drugs. Sharing needles greatly increases your chances of getting the virus.

The vaccine is safe for use during pregnancy. There is no risk of getting hepatitis or other diseases, such as AIDS, from the vaccine. It is given in three doses: the first dose is followed by a second dose in 1 month and a third dose in 6 months.

In some cases, your doctor also may give you hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG). It contains antibodies to the virus. This will protect you against the virus until the vaccine triggers your body to make its own antibodies. HBIG also can be used in pregnancy.

Anyone can become infected with hepatitis B virus. Some people, though, are at increased risk of infection (see box). All teenagers aged 13–18 years who have not already been vaccinated should get the vaccine to protect themselves, their sexual partners, and any children they may have later.

All infants should get the hepatitis B virus vaccine. If you are pregnant and have the virus, your baby will receive HBIG soon after birth. Your baby also will receive the first dose of vaccine. Two more doses of the vaccine will be given later—one at 1–2 months of age and one at 6 months of age. This plan is an effective way to prevent babies from becoming hepatitis B virus carriers.

If you had a negative test result, your baby should get the first dose of vaccine before you leave the hospital. If it cannot be given by then, it should be given within 2 months of birth. Check with the baby's doctor to find out when the second and third dose should be given.

If you were not tested, your baby should get the first dose of vaccine and then you should be tested. The rest of your baby's treatment depends on whether your test results are positive or negative.

Finally...

Infection with hepatitis B virus can damage your health. The test is a safe, easy way to learn whether you have been infected with the virus. If your test results are negative, but you are at increased risk for getting the virus, you should receive the hepatitis B virus vaccine to protect you.

Infection with the virus also can harm your baby. For that reason, all pregnant women should be tested for the virus. If you have a positive test result, your baby will be treated right after birth. All newborns should receive the vaccine.

WHO IS AT RISK ?

Some people are at increased risk for hepatitis B virus. You may need to be vaccinated if you have one or more of these risk factors:

Inject illegal drugs

Are seeking care for a sexually transmitted disease

Are infected with HIV

Have had multiple sexual partners within the past 6 months

Are a health care or public safety worker

Live or have sex with someone who is infected with the virus

Work or live in a home for the disabled

Have certain types of liver or kidney problems.

Have received treatment (clotting factors) for a bleeding disorder

Travel to countries where HBV infection is common

Are in prison

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) [si-to-MEG-uh-lo-vi-rus] is a virus that infects most people worldwide.

- CMV spreads from person to person by direct contact.

- Although CMV infection is usually harmless, it can cause severe disease in persons with weakened immune systems.

- There is no treatment for CMV infection.

- Prevention centers on good personal hygiene, especially frequent handwashing.

What is cytomegalovirus?

- Cytomegalovirus, or CMV, is a common virus that infects most people worldwide.

- CMV infection is usually harmless and rarely causes illness. A healthy immune system can hold the virus in check. However, if a person's immune system is seriously weakened in any way, the virus can become active and cause CMV disease.

What is the infectious agent that causes cytomegalovirus infection?

Cytomegalovirus is a member of the herpesvirus family. Other members of the herpesvirus family cause chickenpox, infectious mononucleosis, fever blisters, and genital herpes. These viruses all share the ability to remain alive, but dormant, in the body for life.

A first infection with CMV usually causes no symptoms. The virus continues to live in the body silently without causing obvious damage or illness. It rarely becomes active for the first time or reactivates (causes illness again in the same person) unless the immune system weakens and is no longer able to hold the virus in check.

Where is cytomegalovirus found?

CMV is found worldwide. The virus is carried by people and is not associated with food, water, or animals.

How do people get infected with cytomegalovirus?

CMV is spread from person to person. Any person with a CMV infection, even without symptoms, can pass it to others. In an infected person, the virus is present in many body fluids, including urine, blood, saliva, semen, cervical secretions, and breast milk.

CMV can be spread by any close contact that allows infected body fluids to pass to another person. CMV can spread in households and child-care centers through hand-to-mouth contact with infected body fluids. CMV can spread by sexual contact, blood transfusions, organ transplants, and breastfeeding. CMV can also be passed from an infected pregnant woman to her fetus or newborn.

Who is at risk for cytomegalovirus?

Anyone can become infected with CMV. Almost all people have been exposed to CMV by the time they are adults, but the virus usually does not make otherwise healthy people sick. However, some people are at increased risk for active infection and serious complications:

- Babies born to women who have a first-time CMV infection during pregnancy

- Pregnant women who work with infants and children

- Persons with weakened immune systems, including cancer patients on chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, and persons with HIV infection

What are the signs and symptoms of cytomegalovirus?

Active infection in otherwise healthy children and adults can cause prolonged high fever, chills, severe tiredness, a generally ill feeling, headache, and an enlarged spleen.

Most infected newborns have no symptoms at birth, but, in some cases, symptoms will appear over the next several years. These include mental and developmental problems and vision or hearing problems. In rare cases, a newborn can have a life-threatening infection at birth. Infants and children who get CMV infection after birth have few, if any, symptoms or complications. When symptoms do appear, they include lung problems, poor weight gain, swollen glands, rash, liver problems, and blood problems.

People with weakened immune systems can have more serious, potentially life-threatening illnesses, with fever, pneumonia, liver infection, and anemia. Illnesses can last for weeks or months and can be fatal. In persons with HIV infection, CMV can infect the retina of the eye (CMV retinitis) and cause blindness.

How soon after exposure do symptoms appear?

Most exposed people never develop symptoms. In those who do, the time between exposure and symptoms is about 3 to 12 weeks.

How is cytomegalovirus diagnosed?

There are special laboratory tests to culture the virus, but testing requires 2 to 3 weeks and is expensive. Blood tests can help diagnose infection or determine if a person has been exposed in the past.

How long does disease from CMV infection last?

- The duration of disease varies, depending on the type of infection and the age and health of the infected person.

- Serious CMV infections that were acquired before birth can cause developmental problems that can affect a child for a lifetime.

- CMV infections in transplant recipients, cancer patients, and persons with HIV infection can be life threatening and require many weeks of hospital treatment. On the other hand, infections in young adults might cause symptoms for only 2 to 3 weeks.

What is the treatment for cytomegalovirus?

There is no specific treatment or cure for CMV infection.

Anti-virus medicines can be helpful in treating CMV retinitis in persons with HIV infection.

How common is cytomegalovirus?

CMV is common worldwide. An estimated 80% of adults in the United States are infected with CMV. CMV is also the virus most often transmitted to a developing fetus before birth.

Is cytomegalovirus an emerging infectious disease?

Yes. Increasing numbers of persons are at risk for CMV infection. Expanding use of child-care centers is increasing the risk to children and staff. Also, the number of people with weakened immune systems is growing because of increases in HIV infection, organ transplantation, and cancer chemotherapy.

How can cytomegalovirus be prevented?

CMV is widespread in the community. The best way to prevent infection is to practice good personal hygiene. Wash hands often with soap and warm water. Avoid mouth contact with the body fluids of young children.

- Chlamydia [kla-MID-ee-uh] is a sexually transmitted bacterial infection.

- Chlamydia can lead to serious reproductive problems, especially in women.

- Chlamydia infection is transmitted through sexual contact with an infected partner. An infected woman can also pass the infection to her newborn during vaginal delivery.

- Chlamydia is often a "silent" infection. Most people with chlamydia have no symptoms and do not seek medical care.

- Once diagnosed, chlamydia is easily cured with antibiotics.

- Prevention centers on 1) use of condoms, and 2) early diagnosis and treatment.

What is chlamydia?

Chlamydia is a SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASE (STD) that can lead to serious reproductive problems, especially in women.

What is the infectious agent that causes chlamydia?

Chlamydia is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, a bacterium.

How do people get chlamydia?

Chlamydia is spread by having vaginal sex with a person who has the infection. It can also be passed from an infected mother to her newborn during vaginal childbirth.

What are the signs and symptoms of chlamydia?

Chlamydia is known as a "silent" disease because three quarters of the women and half of the men infected with the bacterium have no symptoms. Thus, the infection can become very serious before a person even recognizes a problem.

Symptoms in men: Men with symptoms might have a discharge from the penis and a burning sensation when urinating. Men might also have burning and itching around the opening of the penis and/or pain and swelling in the testicles.

Symptoms in women: The few women with symptoms might have a vaginal discharge or a burning sensation when urinating. When the infection spreads to the uterus and fallopian tubes, women can have lower abdominal pain, nausea, fever, pain during intercourse, and bleeding between menstrual periods.

How soon after exposure do symptoms appear?

If symptoms do occur, they usually appear within 1 to 3 weeks of exposure.

How is chlamydia diagnosed?

There are two kinds of laboratory tests to diagnose chlamydia. One involves collecting a small amount of fluid from an infected site (cervix or penis) to detect the bacterium directly. New tests use urine samples to detect small pieces of chlamydia nucleic acid. These are not yet widely available but are making testing much easier, faster, and less painful.

Who is at risk for chlamydia?

Sexually active men and women can be exposed to chlamydia bacteria unknowingly via sexual contact with an infected person. The more sex partners a persons has, the greater the risk of chlamydia infection. Babies born to infected mothers are also at risk.

Sexually active teenagers and young women are especially susceptible to chlamydia bacteria because of the characteristics of the cells that form the inner lining of the cervix. These cells are easily invaded by chlamydia bacteria. In young women, they are exposed on the outer part of the cervix, making them more vulnerable. The cells eventually recede inside the cervix as a woman matures.

What is the treatment for chlamydia?

Chlamydia can be treated and cured with antibiotics. A single dose of azithromycin or a week of doxycycline (twice daily) are the most commonly used treatments. All sex partners must also be treated.

What complications can result from chlamydia?

Untreated, chlamydia infection can progress to serious reproductive and other health problems with both short-term and long-term consequences. Like the disease itself, the damage that chlamydia causes is often "silent."

Untreated chlamydia in men typically causes urethral infection. Infection sometimes spreads to the epididymis (a tube that carries sperm from the testis), causing pain, fever, and potentially infertility.

In women, chlamydia usually begins in the cervix. If not treated, it can spread to the fallopian tubes and cause an infection called pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID can cause chronic pelvic pain, infertility, and potentially fatal ectopic pregnancy (pregnancy outside the uterus). In pregnant women, there is some evidence that chlamydia infections can lead to premature delivery.

Babies who are born when their mothers are infected can get chlamydia infections in their eyes and respiratory tracts. Chlamydia is the leading cause of early infant pneumonia and conjunctivitis (pinkeye) in newborns.

How common is chlamydia?

Chlamydia is the most frequently reported infectious disease in the United States. More than 450,000 cases were reported in 1995. Under-reporting is substantial, though, because most people with chlamydia are not aware of their infections. An estimated 4 million Americans are believed to have it, mostly teenage girls.

Is chlamydia an emerging infectious disease?

Chlamydia is a very common condition in the United States. From 1984 through 1995, reported rates increased from 3.2 to 182.2 cases per 100,000 people. This trend mainly reflects increased screening, increased recognition of symptom-less infections (mainly in women), and improved reporting.

How can chlamydia be prevented?

- Young, sexually active and unmarried persons should be screened for chlamydia yearly.

- Anyone with symptoms should get medical advice, evaluation, and treatment right away.

- Anyone found to be infected should inform all sex partners and be sure they get treated, too.

- Persons being treated for chlamydia infection should not have sex of any kind until treatment is completed as directed for all partners.

- Persons being treated must complete all medications. They should not stop taking prescribed medicines when symptoms disappear.

As a general rule: Sexually active women and men should always use a barrier form of contraception, such as a latex condom. Birth control pills do not protect women from chlamydia.

Rubella [rue-BELL-uh] is a mild but very contagious viral illness. Other names for rubella are German measles and three-day measles.

Rubella is dangerous because of its ability to harm unborn babies. Infection in a pregnant woman can result in :

- miscarriage,

- stillbirth, or

- serious birth defects.

People get rubella by breathing in droplets that get into the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks. Rubella can also spread by direct contact with fluids from the nose or throat of an infected person.

Rubella can be prevented by immunization.

What is rubella?

- Rubella is a mild but very contagious disease that is preventable with a vaccine. Other names for rubella are German measles and three-day measles.

- Rubella is dangerous because of its ability to harm unborn babies. Infection of a pregnant woman can result in miscarriage, stillbirth, or serious birth defects.

What is the infectious agent that causes rubella?

Rubella is caused by the rubella virus.

Where is rubella found?

Rubella is found worldwide.

How do people get rubella?

People get rubella by breathing in droplets that get into the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks.

Rubella can also spread by direct contact with fluids from the nose or throat of an infected person.

What are the signs and symptoms of rubella?

After an incubation period of 14–21 days, German measles causes symptoms that are similar to the flu. the primary symptom of rubella virus infection is the appearance of a rash (exanthem) on the face which spreads to the trunk and limbs and usually fades after three days (that is why it is often referred to as three-day measles).

The facial rash usually clears as it spreads to other parts of the body. Other symptoms include low grade fever, swollen glands (post cervical lymphadenopathy), joint pains, headache and conjunctivitis.

The swollen glands or lymph nodes can persist for up to a week and the fever rarely rises above 38 oC (100.4 oF).

The rash of German measles is typically pink or light red. The rash causes itching and often lasts for about three days. The rash disappears after a few days with no staining or peeling of the skin. When the rash clears up, the patient may notice that his skin sheds in very small flakes wherever the rash covered it.

Forchheimer's sign occurs in 20% of cases, and is characterized by small, red papules on the area of the soft palate.

Rubella can affect anyone of any age and is generally a mild disease, rare in infants or those over the age of 40. The older the person is the more severe the symptoms are likely to be.

Up to one-third of older girls or women experience joint pain or arthritic type symptoms with rubella.

The virus is contracted through the respiratory tract and has an incubation period of 2 to 3 weeks. During this incubation period, the patient is contagious typically for about one week before he develops a rash and for about one week thereafter.

An infected person can spread the disease for as many as 5 days before the rash appears to 7 days after. Infectious children should not attend school or day care.

How soon after exposure do symptoms appear?

In most cases, symptoms appear within 16 to 18 days.

How is rubella diagnosed?

Diagnosis is by blood test or virus culture.

Who is at risk for rubella?

Anyone can get rubella, but unvaccinated, school-aged children are most at risk.

What complications can result from rubella?

Rubella is not usually a serious disease in children, but it can be very serious if a pregnant woman becomes infected. When a woman gets rubella during pregnancy, especially during the first 3 months, the infection is likely to spread to the fetus and cause CONGENITAL RUBELLA SYNDROME (CRS).

Up to 20% of the infants born to mothers infected with rubella during the first trimester of pregnancy have CRS. CRS can result in miscarriage, stillbirth, and severe birth defects.

The most common birth defects are :

- Blindness,

- Deafness,

- Heart damage, and

- Mental retardation.

What is the treatment for rubella?

There is no treatment for rubella. The illness usually runs its course in a few days.

How common are rubella and congenital rubella syndrome?

Since the rubella vaccine was introduced in 1969, cases of rubella and CRS in the United States have remained low. However, cases are reported in persons who were infected in countries that do not routinely provide rubella vaccination (imported rubella). Although CRS is preventable, up to 7 infants are born with CRS each year.

In unvaccinated populations, rubella is primarily a childhood disease. When children are well immunized, adolescent and adult infections become more evident. Since 1994, most rubella and CRS cases were associated with outbreaks among adults, and 75% of all rubella cases were among persons 15-44 years of age.

How can rubella be prevented?

Rubella can be prevented by IMMUNIZATION.

- All children should be vaccinated to protect themselves and others from rubella. The rubella vaccine is part of the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine series given to children beginning at 12 months of age.

- To help protect unborn babies from CRS, women must be immune to rubella before they become pregnant. Reproductive-aged women should find out their immunization status and receive rubella vaccine if needed. Usually, a blood test will be done during pregnancy to determine if a woman is protected against rubella. Any pregnant woman who has been exposed to rubella should be referred to her health-care provider.

As is the case with all immunizations, there are important exceptions and special circumstances. Health-care providers should have the most current information on recommendations about the rubella vaccine.

Visitor

Labels

- Carcinoma (2)

- Dysmenorrhoea (4)

- Endometriosis (4)

- Female Genital Infection (3)

- Fluor Albus (4)

- General (3)

- Genital Prolapse (4)

- Gynecology (8)

- Infectious Disease in Pregnancy (13)

- Infertility (10)

- Menopause (3)

- Menstrual Disorder (10)

- Myoma Uteri (3)

- Obstetrics (13)

- Pelvic Floor (4)

- Pelvic Inflamatory Disease (3)

- Physiology of Human Reproductive System (4)

- Pregnancy (2)

- Sexually Transmitted Disease (6)

- Uterine Bleeding (4)

Followers

Facebook Badge

Copyright © 2009 Complicated Girl. All Rights Reserved.